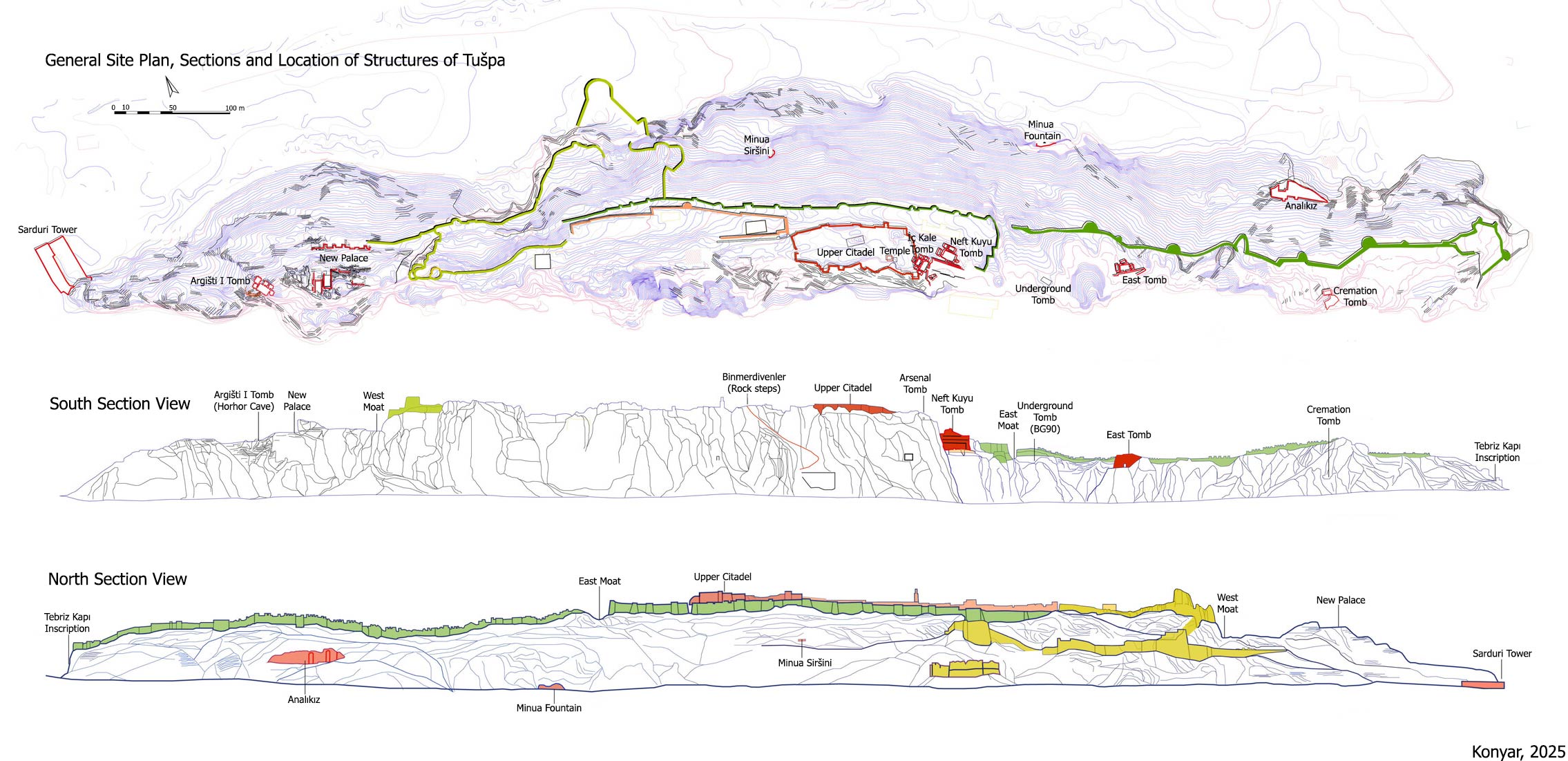

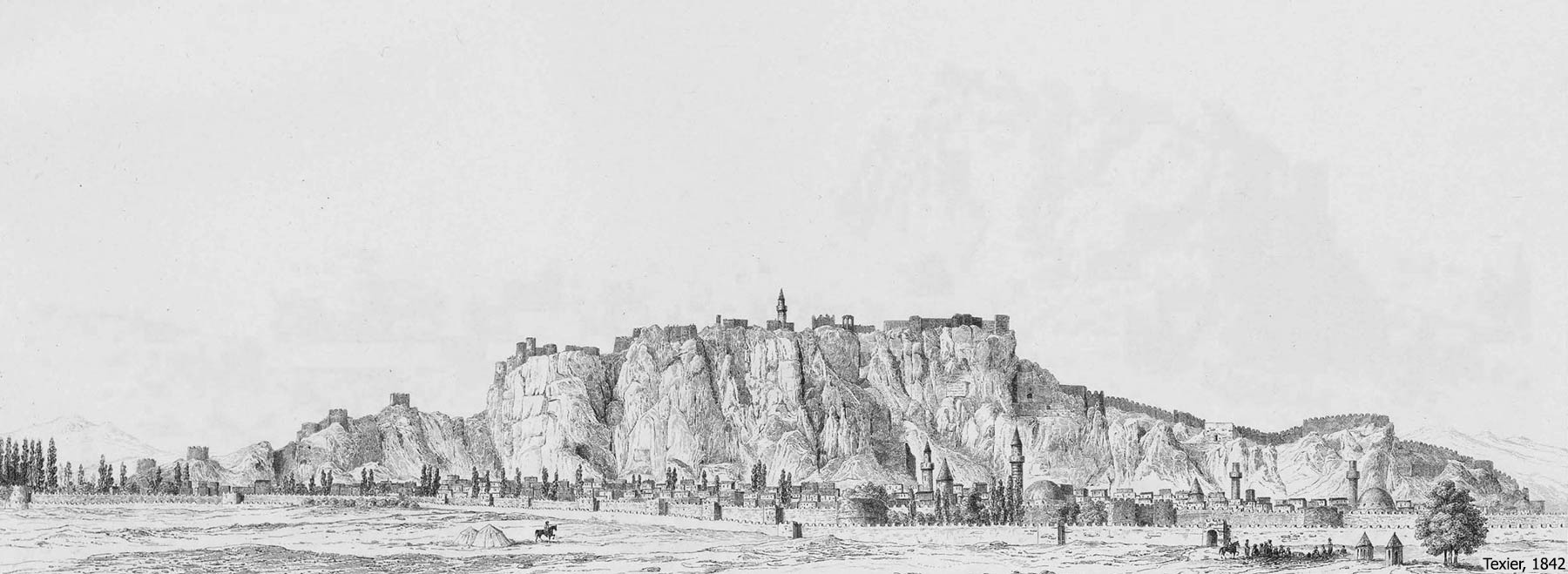

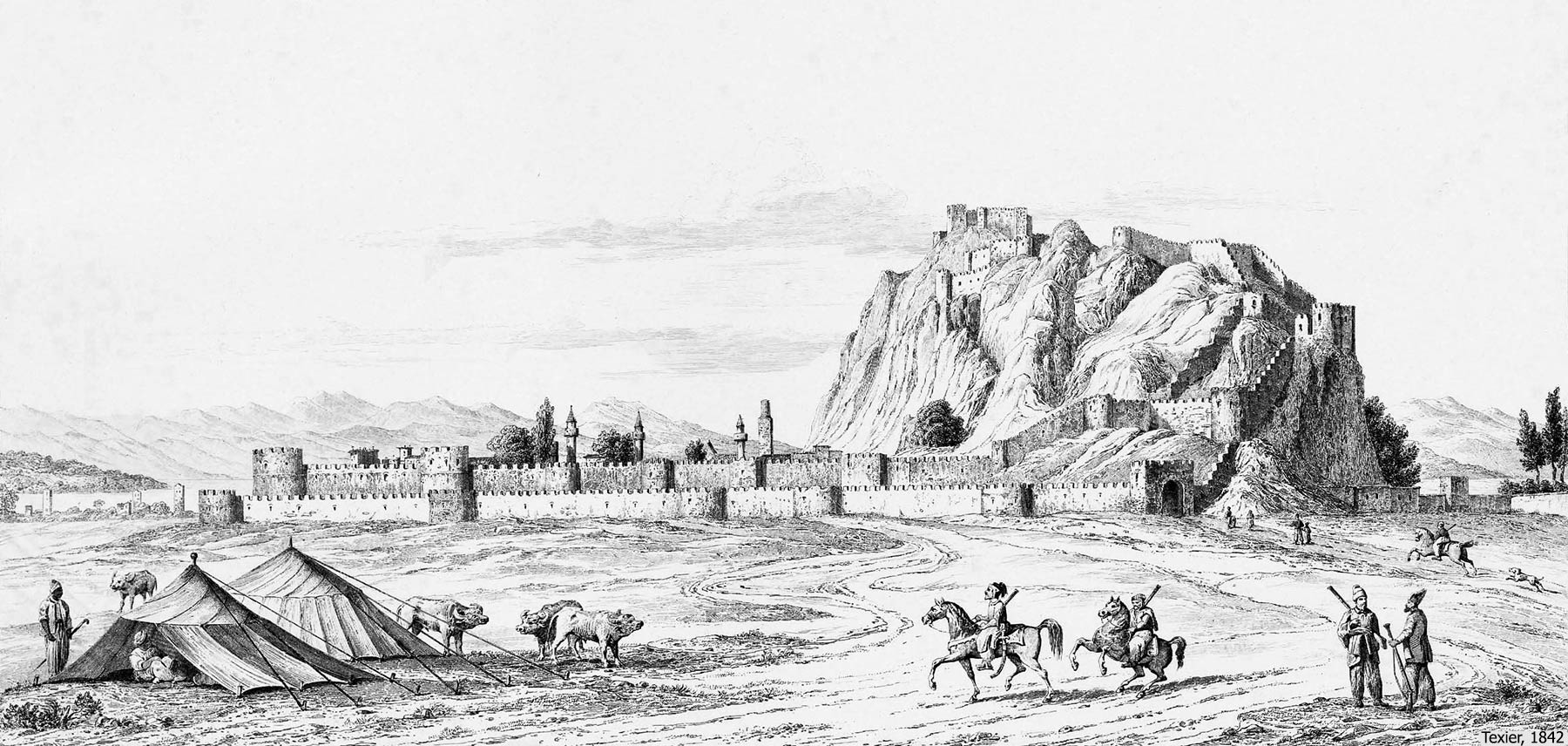

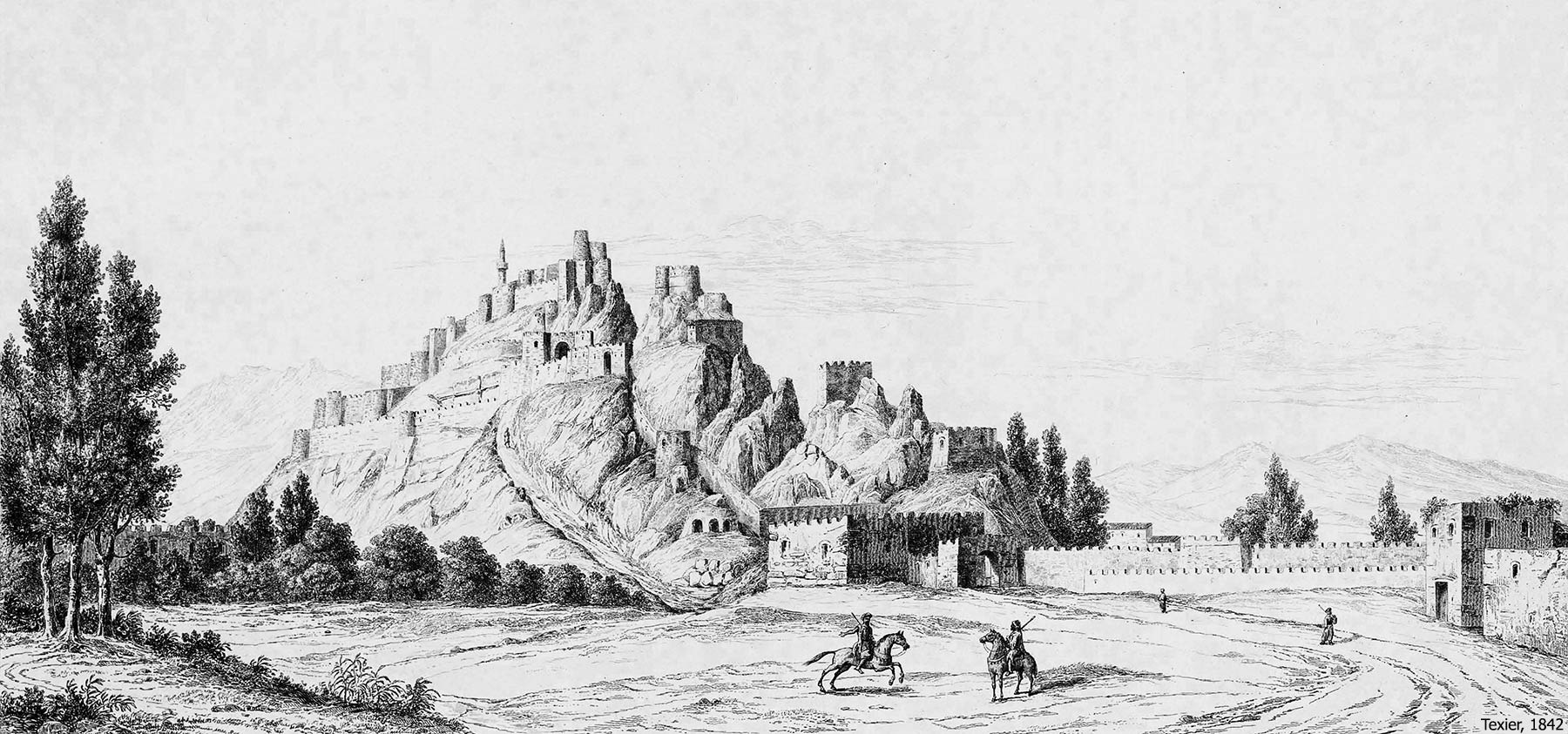

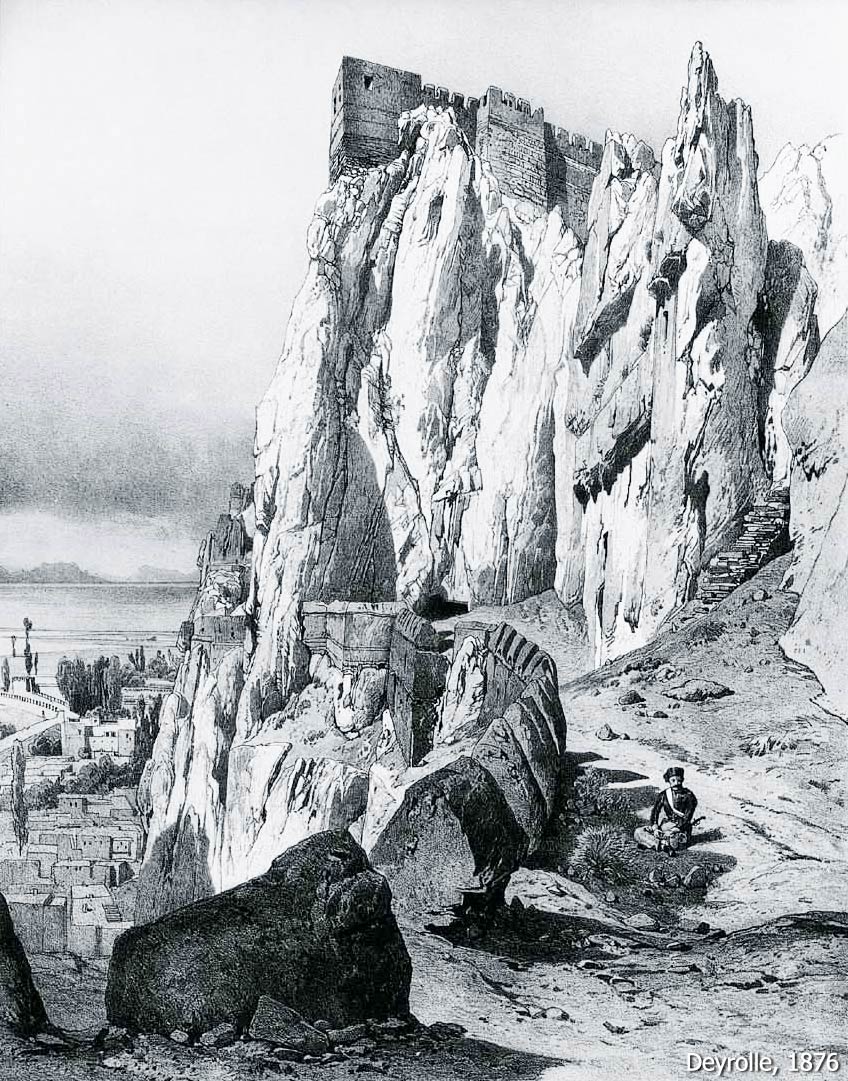

Tušpa, the capital of the Urartian Kingdom was established on and around a rocky hill rising on the shore of Lake Van, about 5 km west of today’s city center of Van. It is generally known as Van Kalesi (Van Fortress). The settlement consists of a citadel built atop a hill 1,350 meters long and 70–80 meters wide, oriented east-west, and the lower city that surrounds it. Archaeological evidence indicates that the site’s habitation dates back to the 3rd millennium BCE. The settlement in the lower city continued until the early 20th century. The Urartian citadel was founded in the mid-9th century BCE by King Sarduri I. The city, referred to as Tušpa in Urartian inscriptions, may be associated with the Urartian goddess Tushpuea. The modern name Van is thought to have derived from Biainili or Biane, the name Urartians gave themselves and their land.

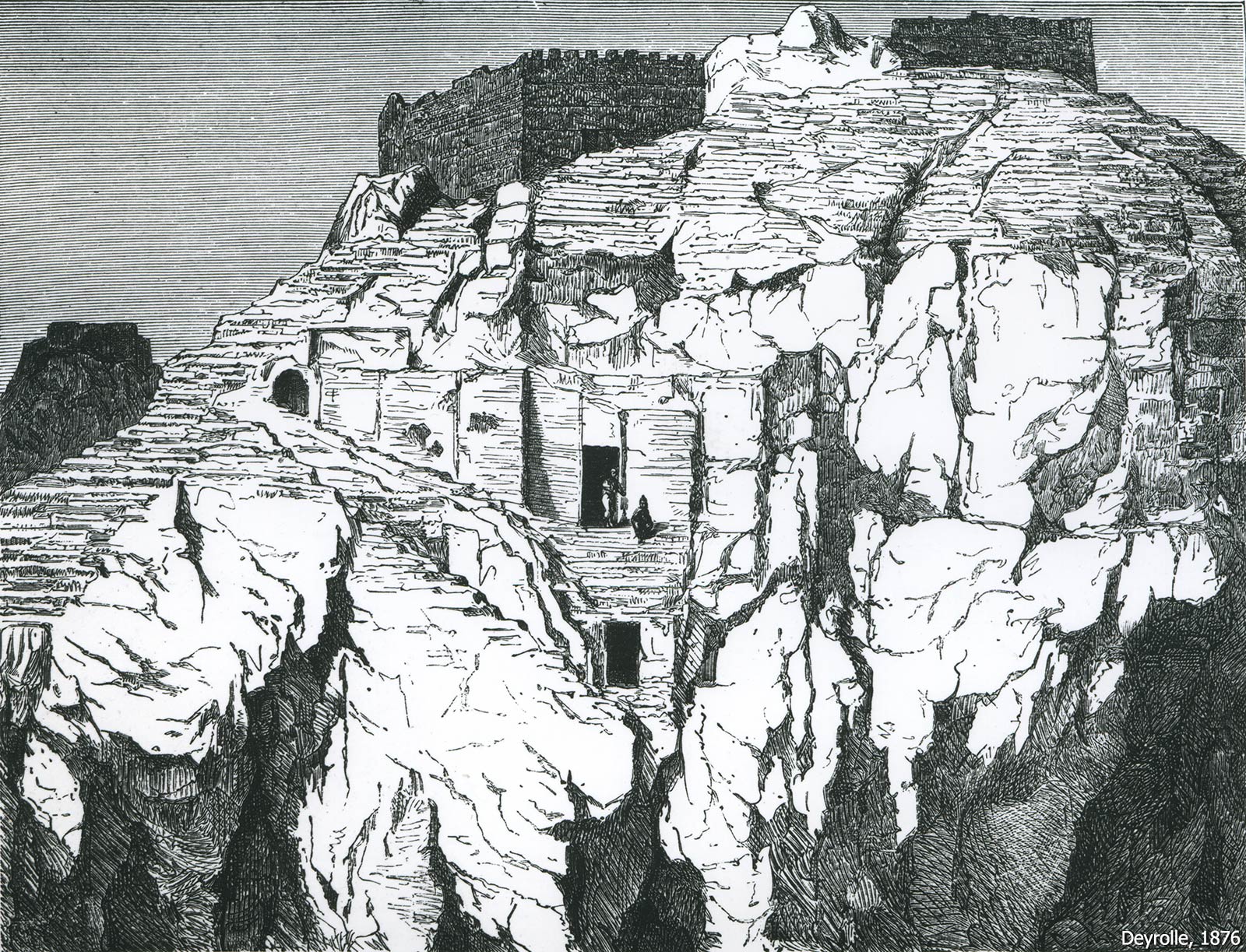

The first modern research in the city was conducted in 1827 by F. E. Schulz. Following this, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the region attracted many foreign researchers. After 1959, excavations were mostly carried out by local scholars. Within the Van Fortress are royal tombs, sacred areas, remnants of temples and palace structures, and numerous Urartian inscriptions carved into the rocks. The citadel and inner fortress are surrounded by high walls, further fortified by two large moats cut into the eastern and western sides of the hill. The southern side of the hill is impassable due to steep cliffs, while the more gently sloping northern side descends in terraces. Access to the fortress is via a ramped road on the northwest. The Urartian-era walls were built to match the structure of the bedrock. The visible walls today include additions from the Seljuk and Ottoman periods. Compared to the remains of palaces and temples, which survive only at foundation level, the sacred areas and tombs carved into rock have remained more intact.

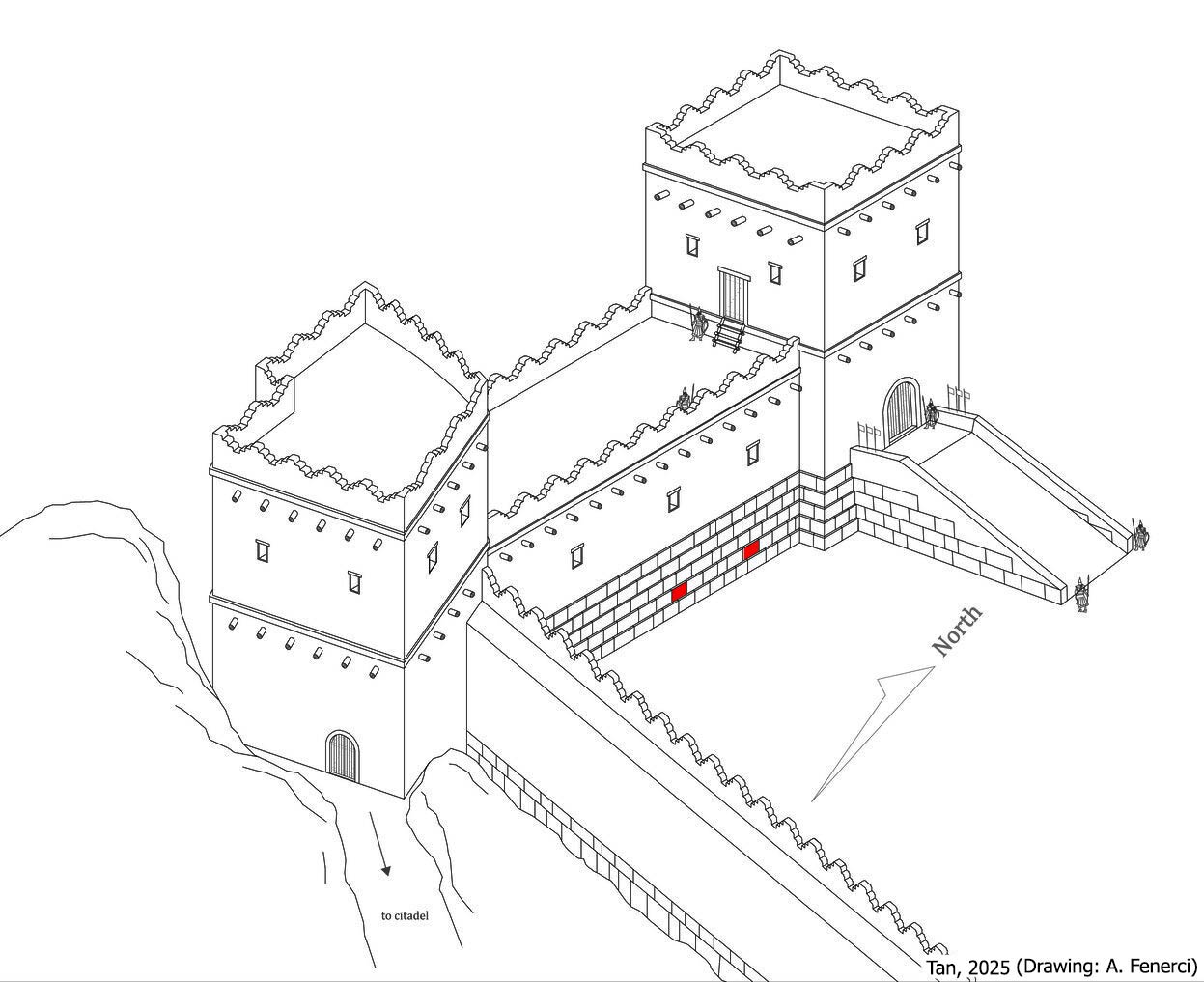

Sarduri Tower (Sardursburg – Sardurburcu)

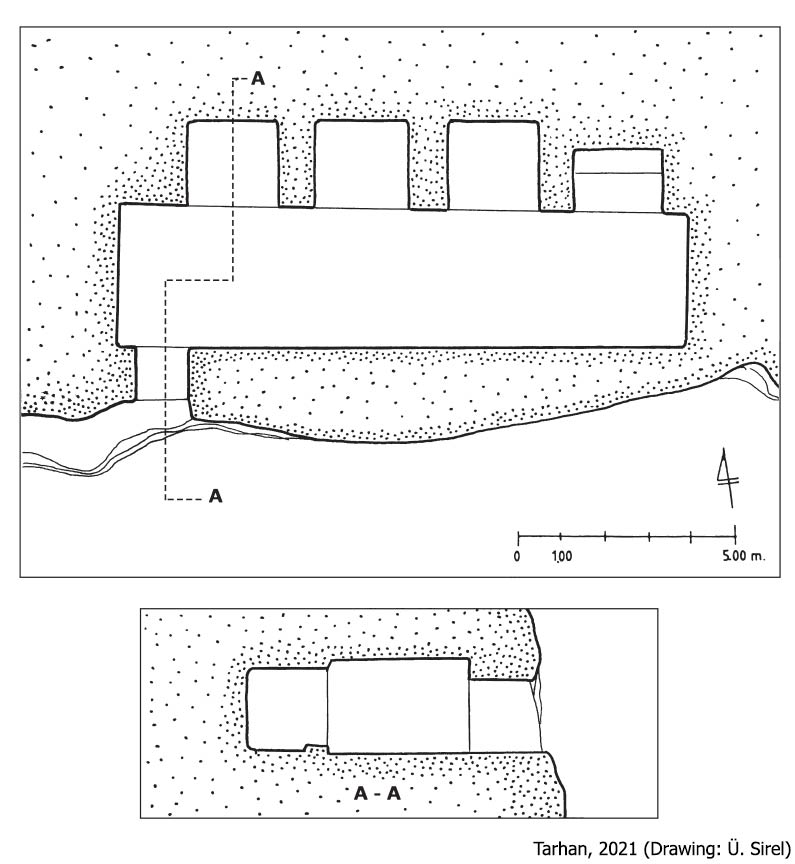

Located at the westernmost end of the citadel, this rectangular structure measures approximately 47 x 12 meters. Only the 4-meter-high foundation survives today. Known as Sardursburg (Sardur Tower) or Madırburç, it bears identical inscriptions (A 1‑1A‑F) on its east and west faces stating it was built by Sarduri I, the founder of the Urartian Kingdom. It is the oldest known royal structure in Tušpa. Although early scholar Lehmann-Haupt referred to it as a “burg/tower” and it is commonly cited as such in literature, its exact function remains uncertain. Various scholars suggest it could have been a fortification structure, the foundation of a palace or temple, or even a quay or breakwater while the lakeshore extending to the slopes of the citadel hill in ancient times. Recent findings indicate that the Sardur Tower was built in three phases and functioned both as an access gate to the citadel and a fortification feature.

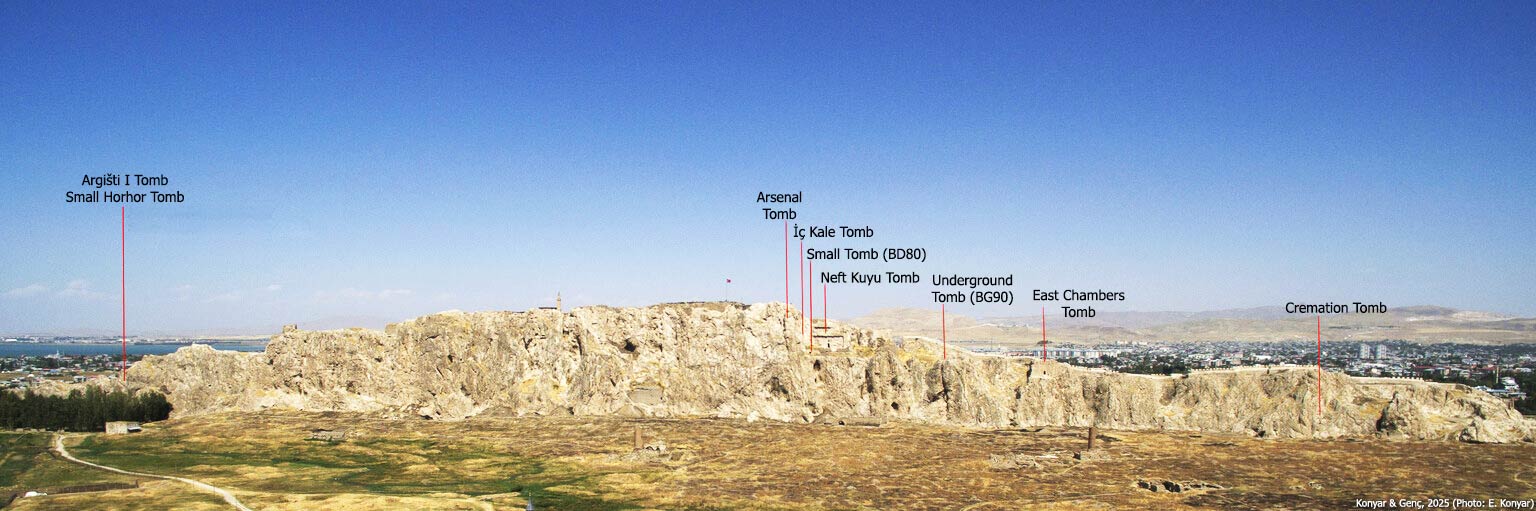

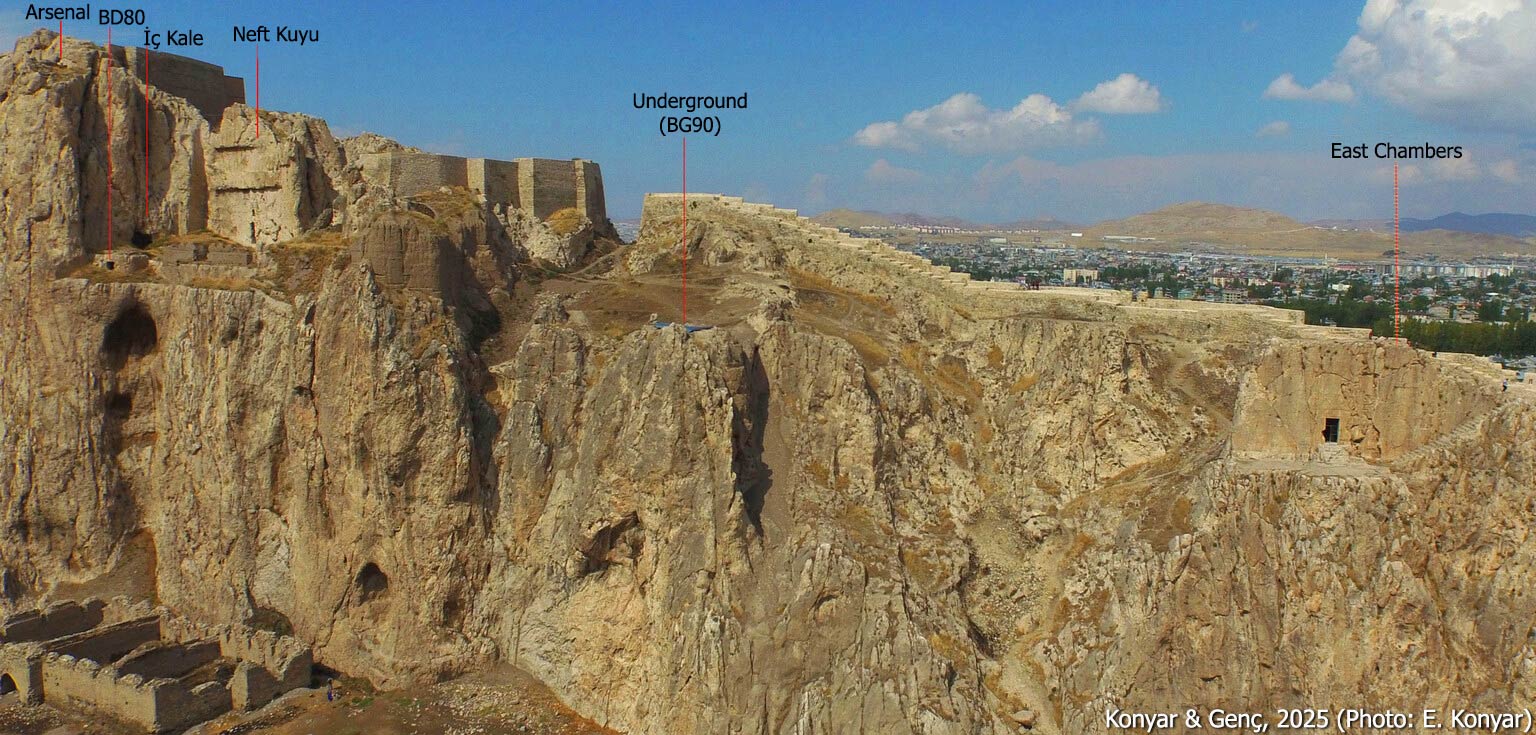

Rock-Cut Tombs

There are eight rock-cut tombs on Van Fortress, all carved directly into the bedrock. They are located along the southern cliff face, with the exception of the Inner Fortress Tomb, all possessing south-facing entrances. With the exception of the Tomb of Argišti I, none of the tombs bear inscriptions identifying their intended occupants. However, they are generally attributed to Urartian royalty or members of the ruling elite based on their typology and architectural features.

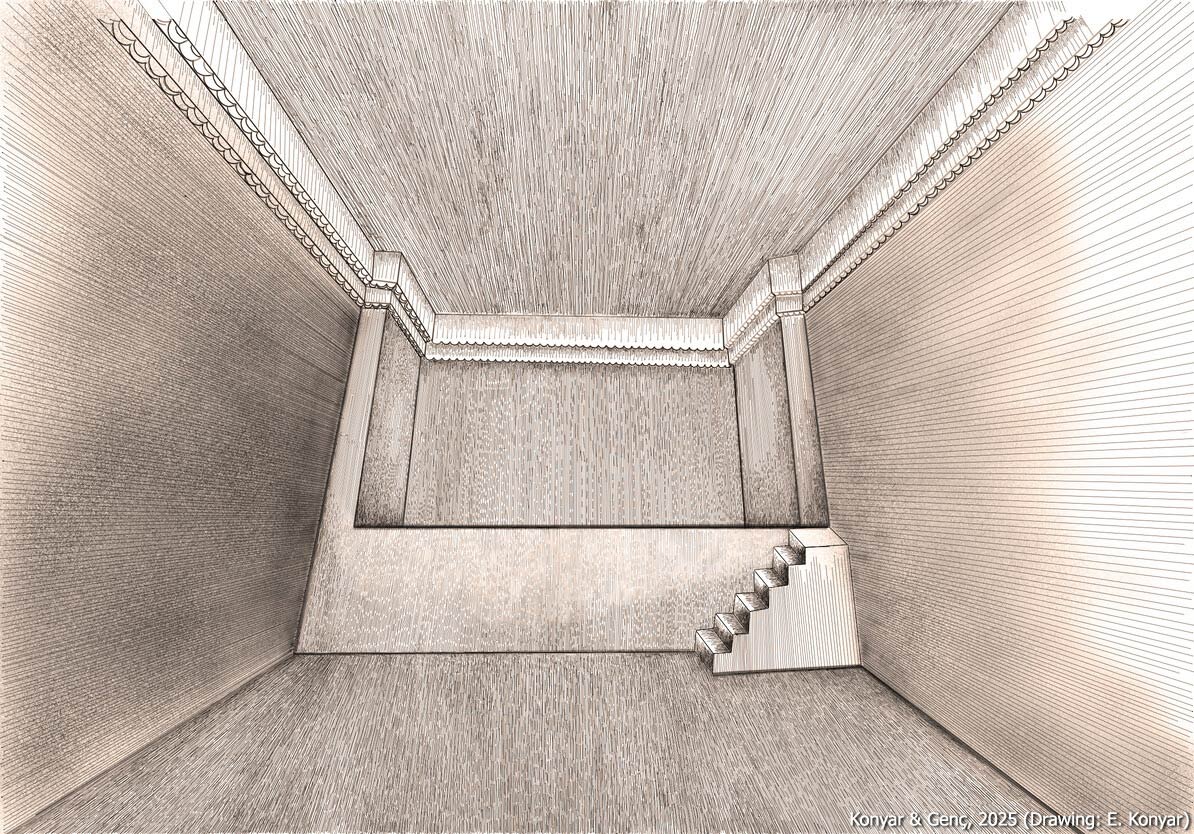

Tomb of Argišti I (Horhor Cave)

This is the westernmost tomb on the Van citadel, situated approximately 150 meters west of the Western Ditch and carved into the southern face of the bedrock. Access to the tomb is via a stairway carved into the rock descending from the cliff top to the entrance. A prominent inscription (A 8‑3) covering the entrance façade identifies the tomb as that of Argišti I, son of Minua, making it the only tomb at the site for which ownership is definitively known. The tomb is also referred to in the literature as the Horhor Tomb or Horhor Cave, named after a nearby spring known as Horhor Fountain, mimicking the sound of gurgling water. The extensive inscription, arranged in eight columns along the stairs and entry wall, narrates the military and political achievements of Argišti I. The tomb comprises a rectangular main chamber of 62 m² with a flat ceiling, and five side rooms: two to the north, one to the east, and two interconnected rooms to the west. A total of 34 niches are present on the chamber walls.

Small Horhor Cave

Situated directly beneath the Tomb of Argišti I, it is accessed via a narrow staircase of twenty steps carved into the bedrock. Though evidently constructed later than the Tomb of Argišti I, the identity of its occupant remains unknown. The tomb consists solely of a 38 m² rectangular chamber. Four large niches are carved into the rear wall.

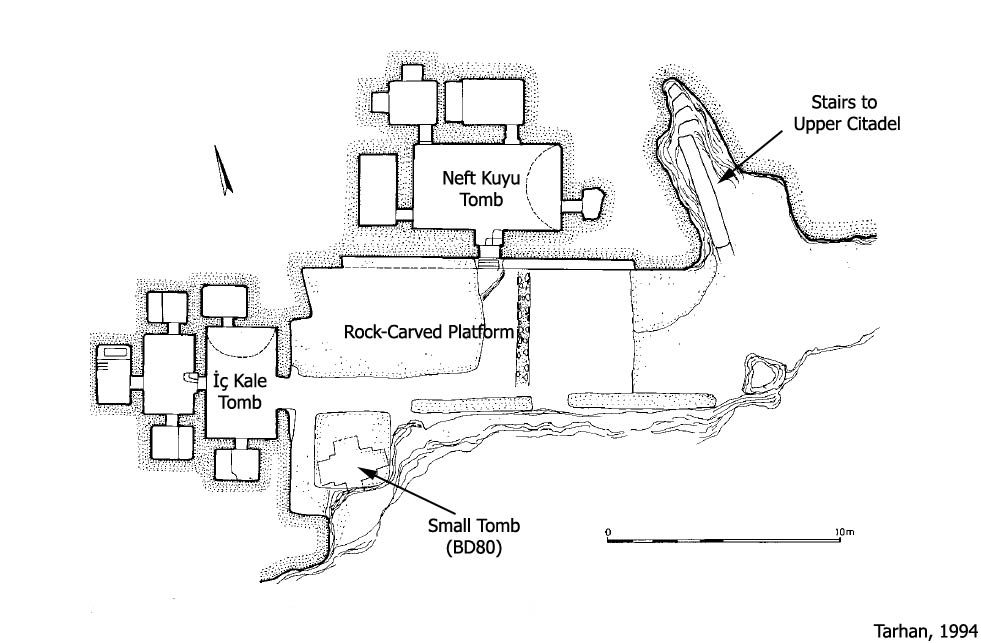

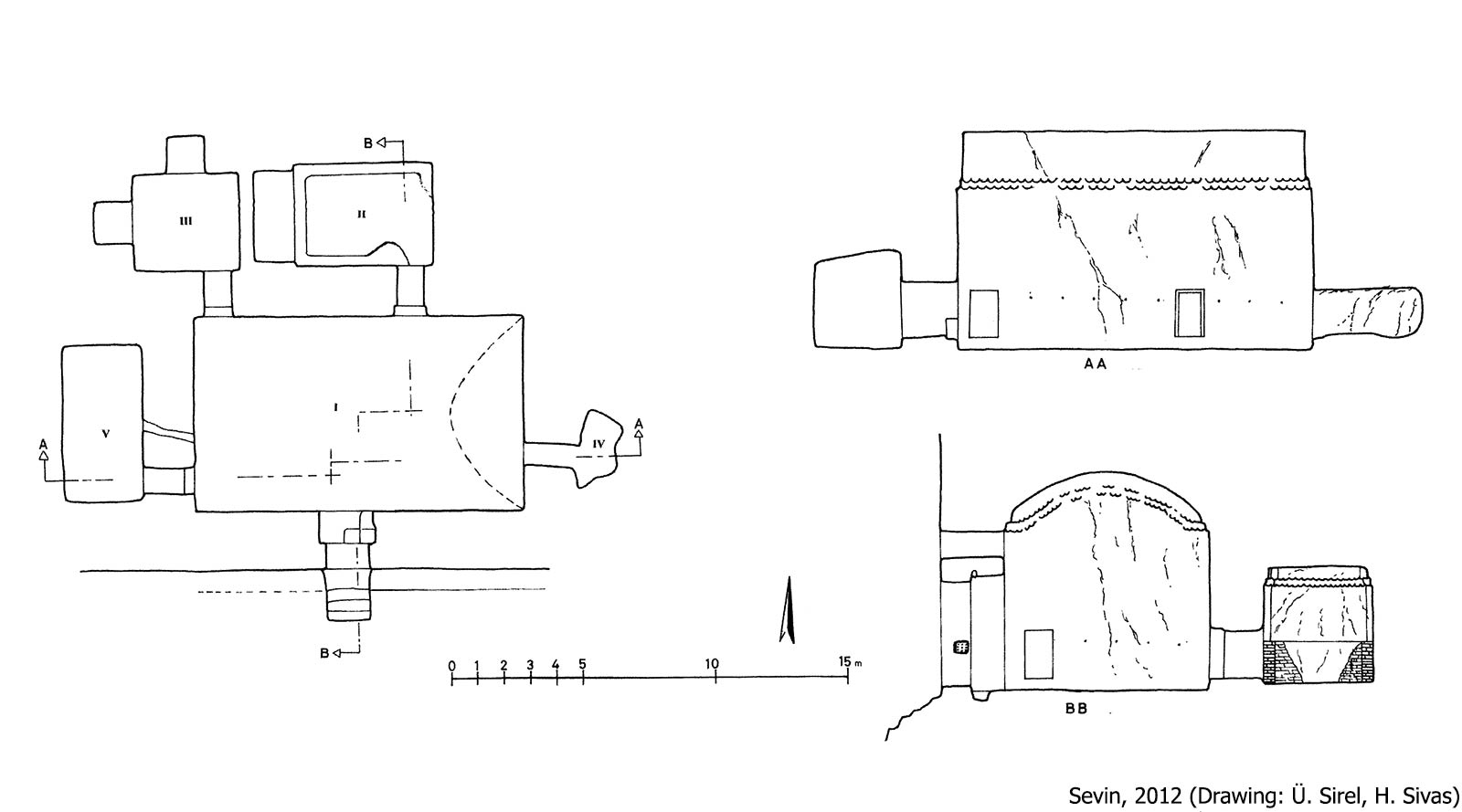

Neft Kuyu Tomb

Located just below the inner fortress at the southeastern end. The tomb derives its name Neft Kuyu (Oil Well) from the Ottoman era when the tomb was reportedly used to store oil. Some scholars regard it as the oldest monumental tomb within the citadel and ascribe it to Sarduri I. Due to its prominent location and expansive 20-meter-wide façade; it remains the most visually commanding tomb on the citadel and is visible from great distances. The bedrock at this location was extensively carved to create the tomb and a 140 m² ceremonial platform in front, likely used for ritual purposes. The south-facing tomb consists of multiple chambers. The main hall, entered via a 3.5-meter-high doorway, measures approximately 90 m² and features a barrel-vaulted ceiling rising to 7.5 meters. Two rooms adjoin the northern wall, while the eastern and western walls each contain one room. The workmanship in the northern rooms is notably more refined. It is postulated that the sarcophagus of the tomb’s occupant once rested on a niche in the left chamber. The room to the east appears to have been left unfinished.

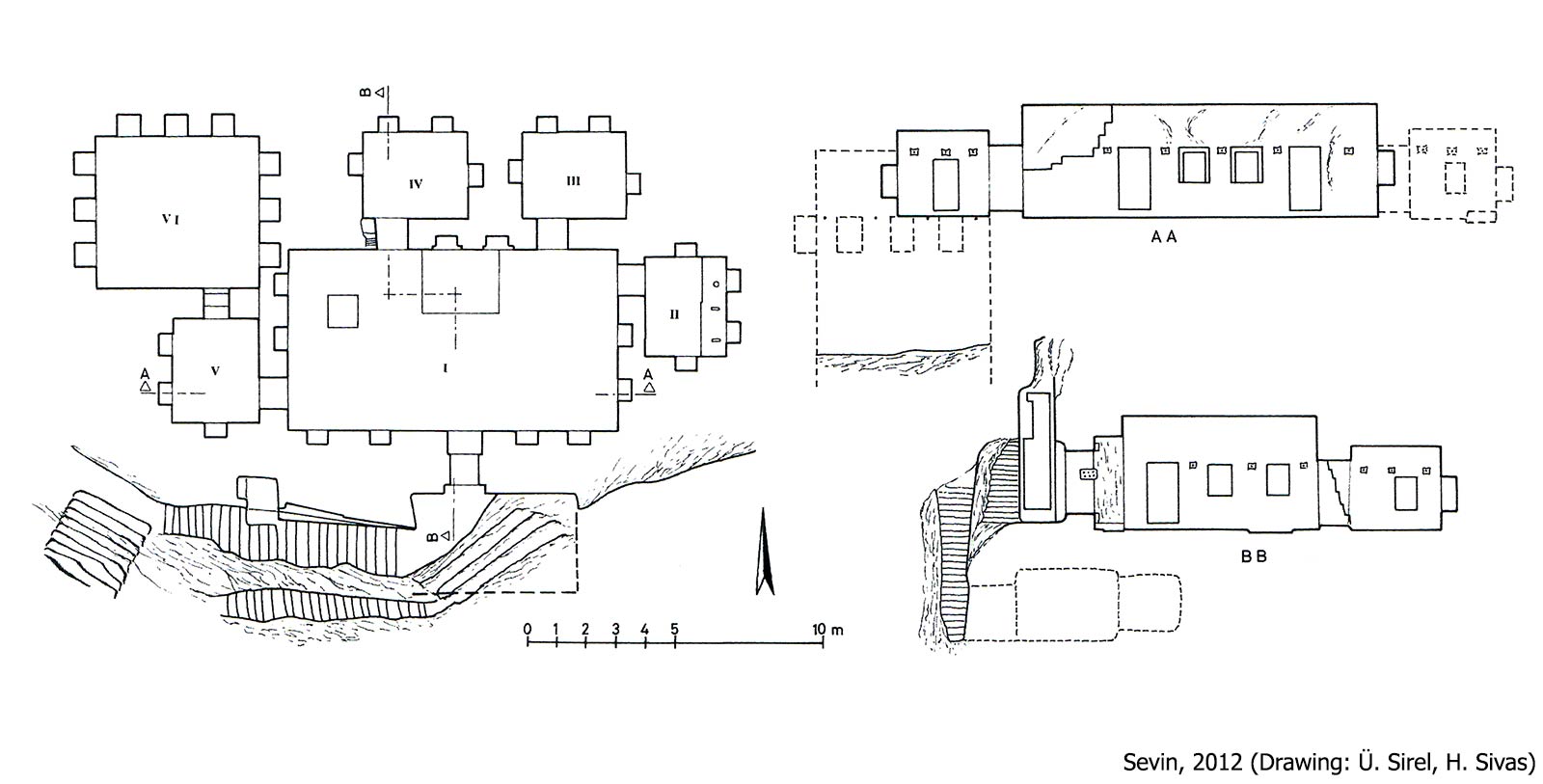

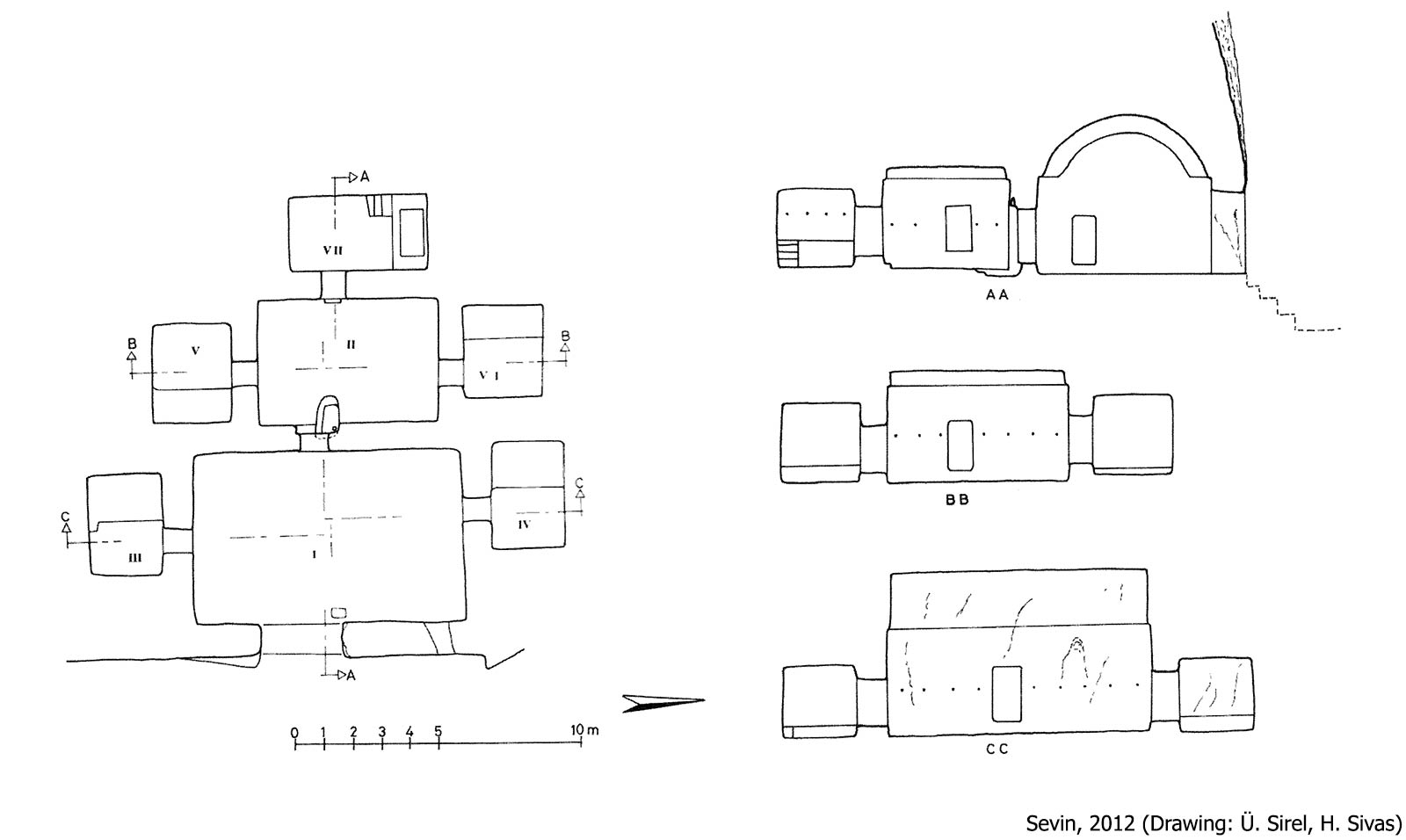

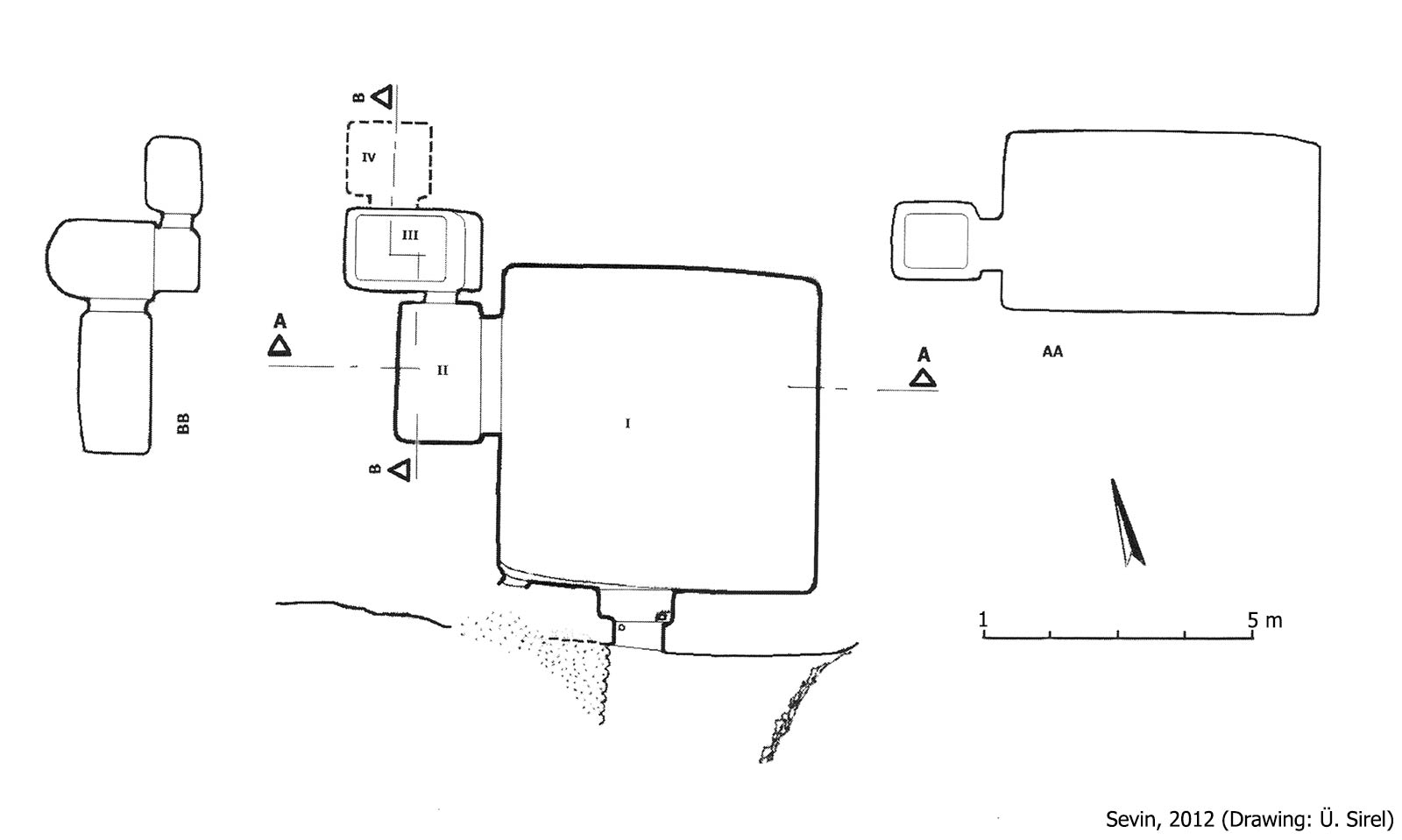

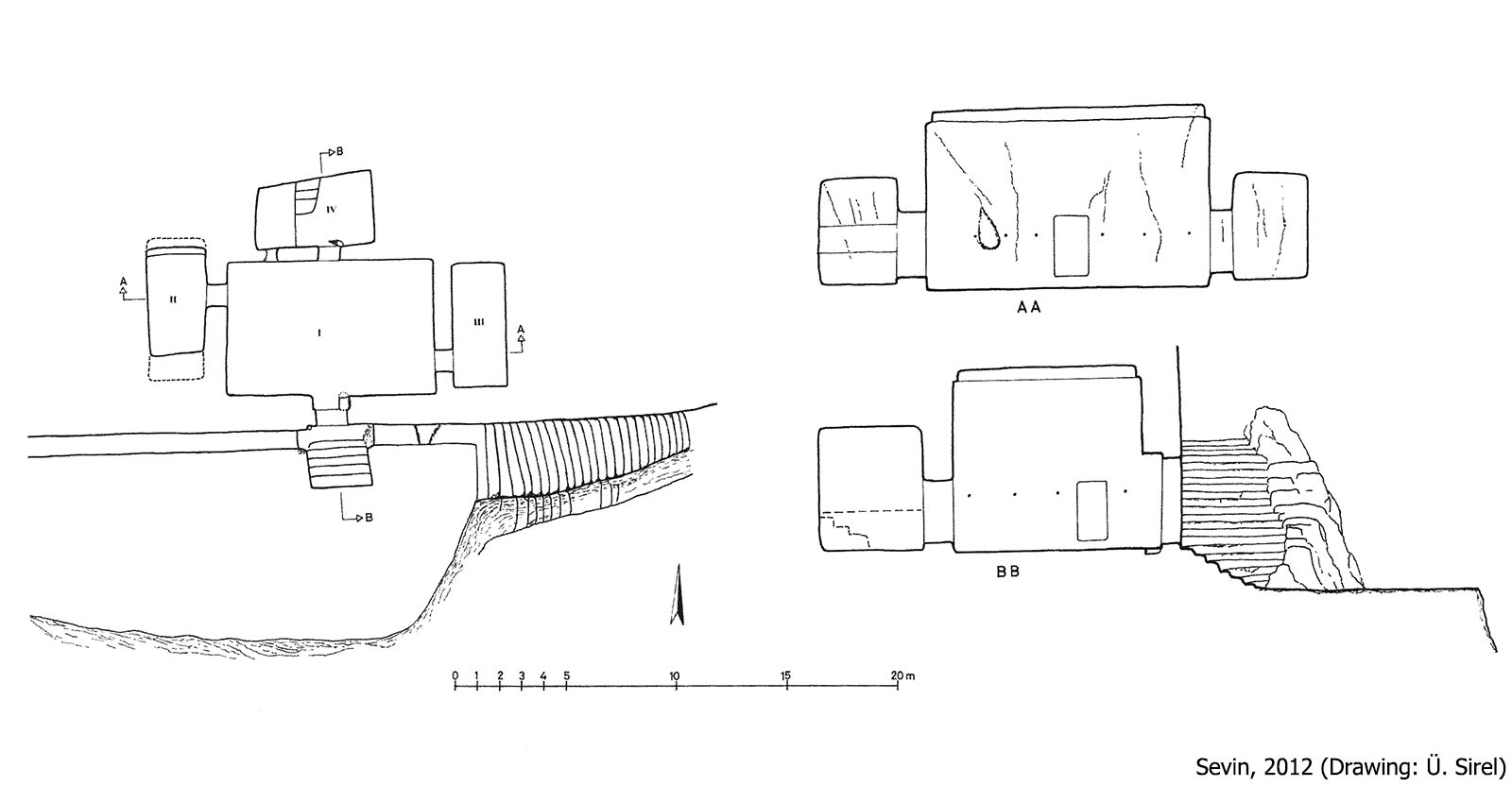

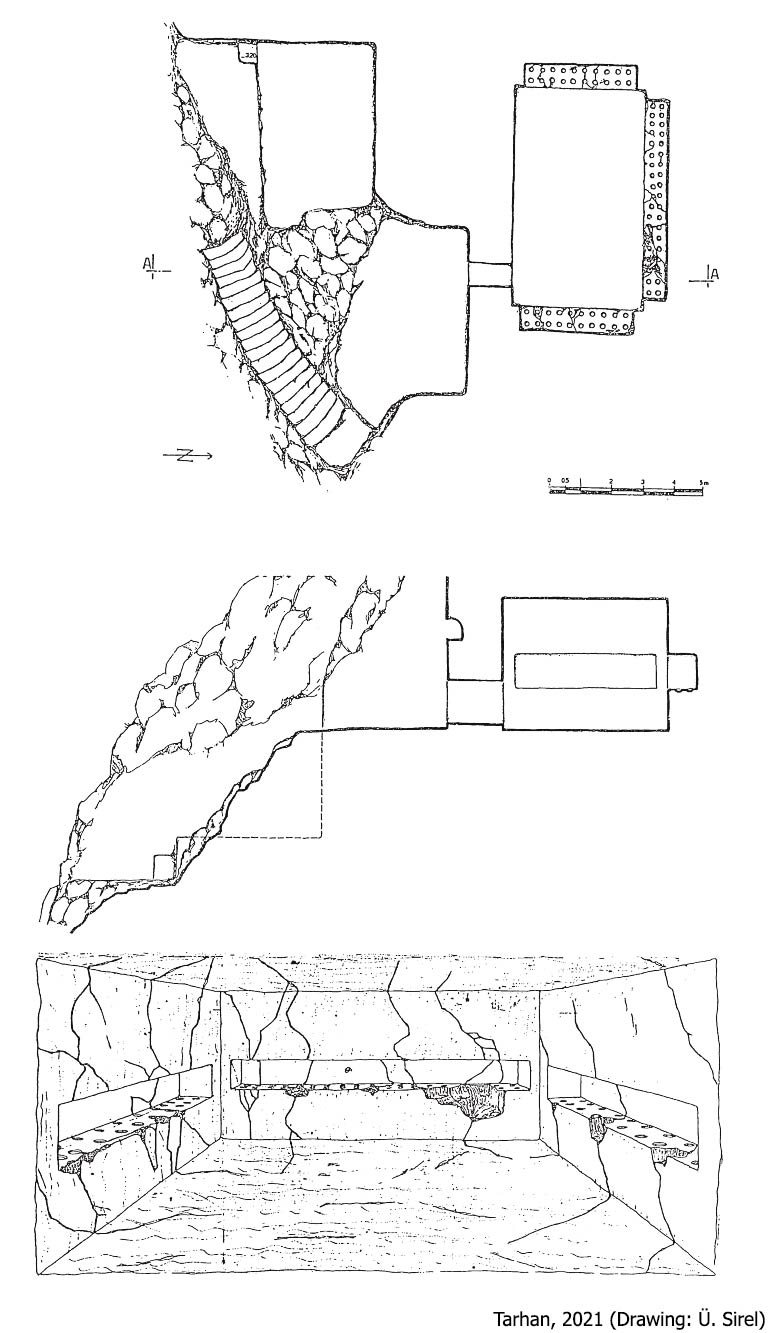

İç Kale (Inner Fortress) Tomb

This tomb is carved into the rock face west of the ceremonial platform in front of the Neft Kuyu Tomb. Its east-facing entrance distinguishes it from other tombs at Van Fortress. Although more eroded than the Neft Kuyu Tomb, it may have been constructed later. Also known as the Founders’ Tomb, early scholars in the 19th century hypothesized that it belonged to the founders of the fortress, based on its presumed antiquity. The exterior appears to have deteriorated due to natural causes. The tomb comprises two consecutive halls, each with flanking side rooms, and a rear burial chamber. According to Sevin, structural damage during construction caused the abandonment of the first hall and led to the excavation of a second one behind it. Tarhan has proposed that the tomb may have been intended for Minua and his son Išpuini, who are known to have ruled the kingdom jointly for a period.

Small Rock Tomb (BD80)

Situated approximately two meters below the ceremonial platform in front of the Inner Fortress and Neft Kuyu tombs, this single-chamber tomb has a south-facing entrance. Three large niches are carved into the side and rear walls. It is the smallest rock-cut tomb at Van Fortress.

Arsenal Tomb

Located approximately 30 meters above the platform where the Inner Fortress Tomb stands, this tomb takes its name from its use as an ammunition depot during the Ottoman era. It differs in architectural plan from the other monumental tombs. Entry is gained via a south-facing door that leads through a 1-meter-long passage into a square room of approximately 20 m². A small chamber, scarcely large enough to qualify as a room, is found in the western wall, leading through its northern wall into a second, presumed burial chamber. This chamber in turn connects to a third, even smaller niche or chamber in its north wall.

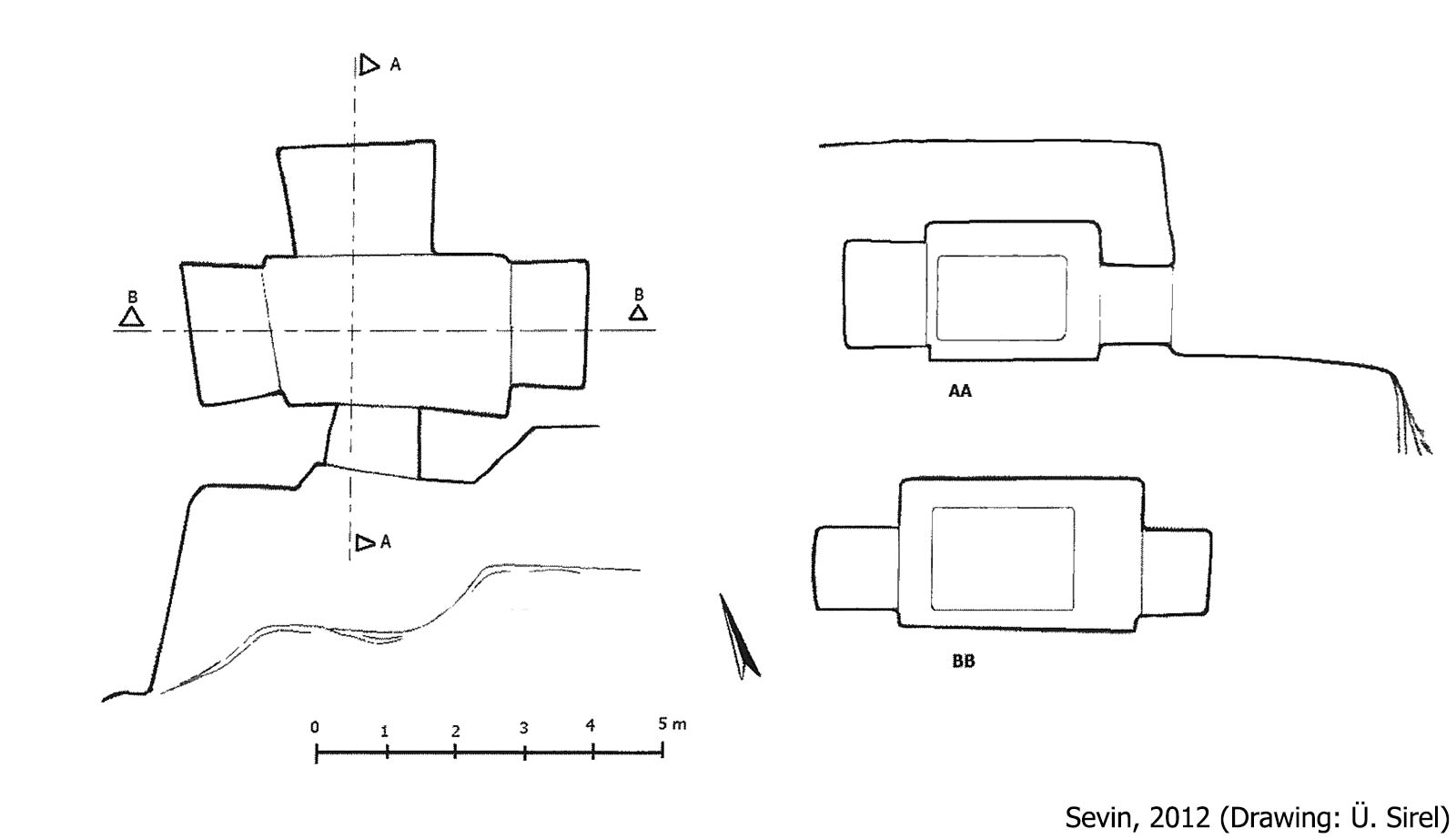

East Tomb / East Chambers Tomb

Located approximately 40–50 meters east of the East Ditch on the south-facing rock surface, this tomb is also referred to as the East Chambers. An 8-meter-wide rock platform lies in front of the tomb, and the stairs descending to it are carved into the bedrock. The entrance leads to a rectangular hall of about 60 m², with a 6-meter-high flat ceiling. Three rooms open off the main hall—one at the back and one on each side. Although it is undoubtedly a royal tomb, its ownership is debated, with suggestions including Sarduri II, Rusa I, or Minua.

Cremation Tomb

It is the easternmost tomb of the Van citadel, features a south-facing entrance, which is accessed by rock-cut stairs. Uniquely, it is situated at a lower elevation closer to the lower city. The tomb consists of a single rectangular chamber of approximately 20 m². Along the rear and side walls are elongated horizontal niches, each containing round recesses—78 in total—intended to place urns containing the cremated remains of the deceased. This tomb offers critical evidence that the Urartians practiced both inhumation and cremation.

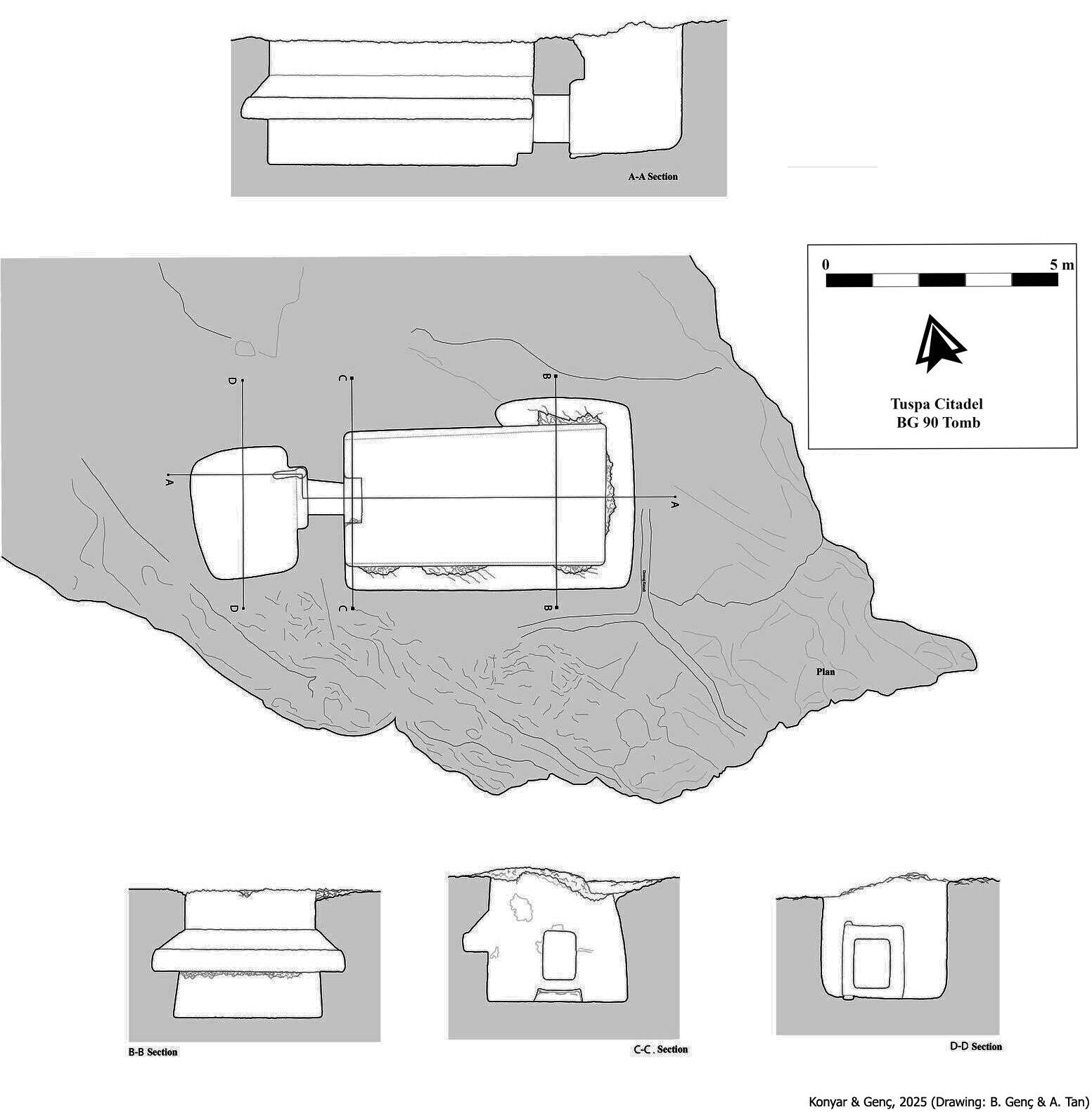

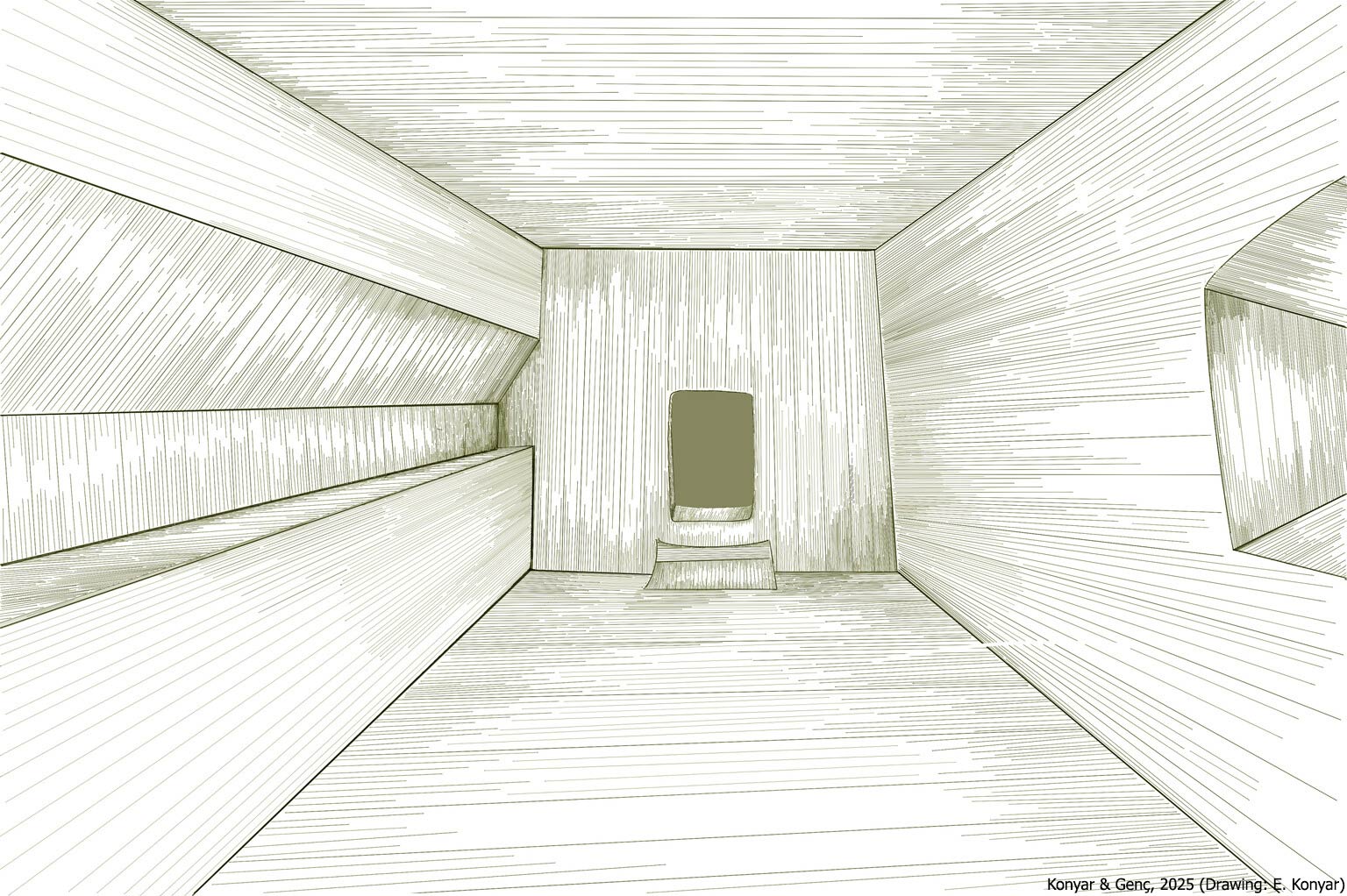

Underground Rock-Cut Tomb (BG90)

Located roughly 40 meters east of the East Ditch, this tomb is distinct from the other tombs in Van Fortress as it is cut underground into the bedrock. Unearthed during excavations conducted in 2016, the tomb comprises a vertical entry passage (dromos) and a main burial chamber, measuring 5.8 × 3.15 meters. Niches approximately 50 cm deep and 40 cm high are cut into the southern and eastern walls, and partially into the northern wall. The niche was not extended across the entirety of the north wall, likely due to instability in the bedrock. The layout is reminiscent of the Cremation Tomb. The nature of the superstructure—if any—that once surmounted this chamber remains unknown. Comparisons to analogous tombs in northern Iran suggest that a rock-carved roof may have once existed but collapsed over time.

Assyrian-Inscribed Stele Niche

Located on the eastern face of the East Ditch, this niche is heavily damaged; however, the presence of a socket at its base indicates that it once housed an inscribed stele. Fragmentary inscriptions preserved on the side walls of the niche are partially legible and appear to refer to a list of sacrificial offerings. Composed in the Assyrian language, the text confirms that the monument dates to the reign of Sarduri I and represents the oldest known inscription and sacred precinct at Tušpa.

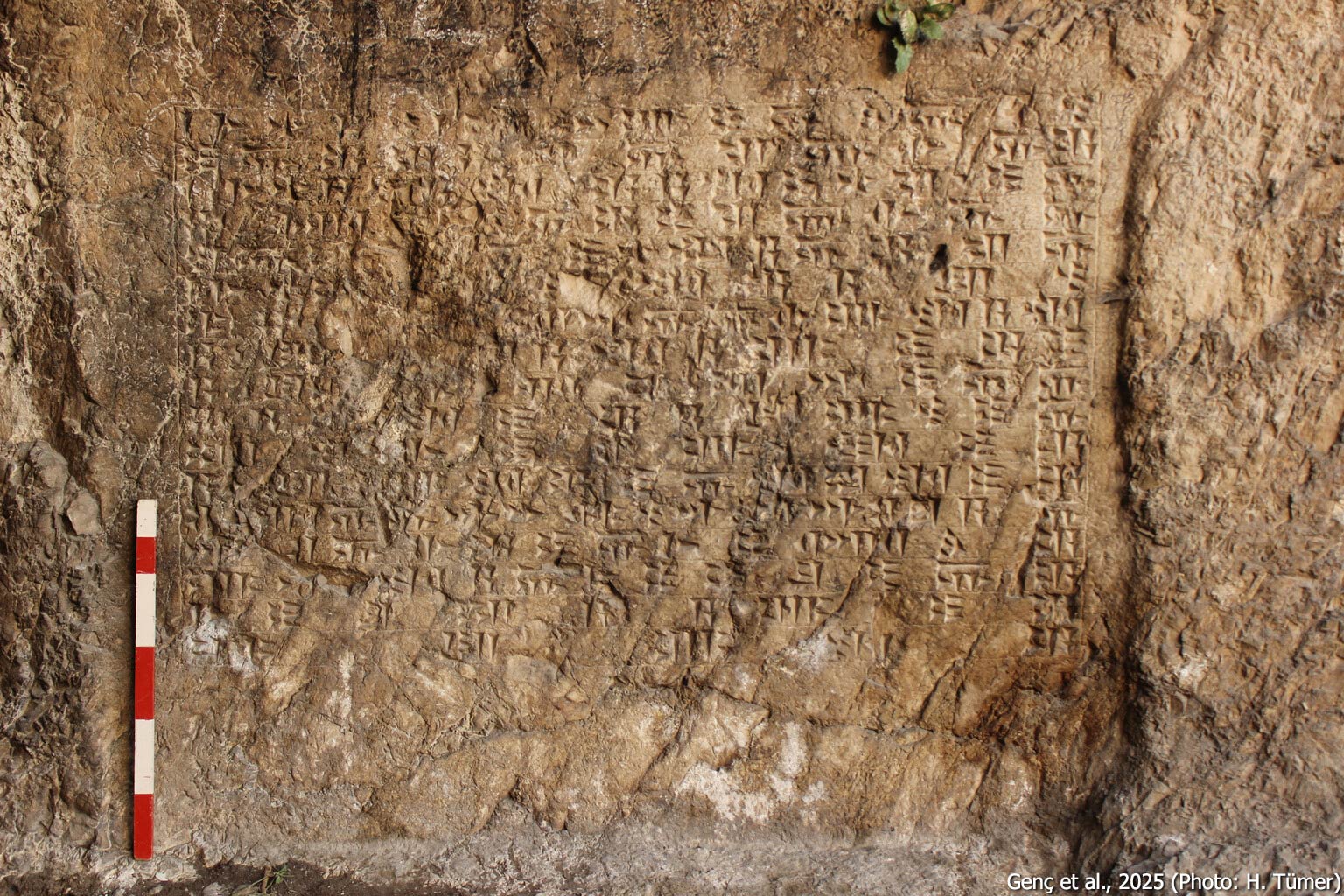

Minua Hall (Minua Siršini)

Located roughly at the midpoint of the northern slope of the hill, this expansive chamber is carved directly into the bedrock. An inscription on the wall to the west of the entrance (see A 5‑68) attributes the construction to King Minua. Within the inscription, the structure is referred to as Minua Siršini. Based on the context of the text, the term siršini is interpreted to mean “animal pen” or “enclosure for livestock.” This interpretation also explains the relatively low ceiling height of 2.5 meters in the otherwise sizeable chamber, which measures approximately 166 square meters. Scholars have proposed that the hall was used to house animals intended for sacrificial rites, particularly those associated with ritual practices. The entrance portal measures 8.5 meters in width and 2 meters in height. Excavations have revealed two separate stele sockets—one directly in front of the entrance and another within a niche to its left. Furthermore, a stone block inscribed with Urartian text—currently housed in the Tbilisi Museum and discovered at Van Fortress—is believed to have originally belonged to this structure. The inscription on that block (A 5‑69) contains the term siršini and is identical to the first five lines of the rock inscription at the entrance to Minua Hall. A wide platform hewn from the bedrock directly in front of the hall may have functioned as a staging area for sacrificial ceremonies.

Minua Fountain

This spring emerges at the mouth of a natural cave located on the northern foothill of the fortress. Although no architectural elements of the fountain have survived, three nearly identical inscriptions—each engraved within separate panels at different heights on the rock surface—attest that the installation, referred to as a tarmanili, was commissioned by Minua (see A 5‑58). Comparative analysis with similar inscriptions and water installations found in present-day Azerbaijan has led scholars to interpret the term tarmanili as meaning “fountain” or “spring structure.” Although excavations have confirmed that the Horhor Fountain—located beneath the Tomb of Argišti I—is also a product of the Urartian period, no associated inscription has been identified to date.

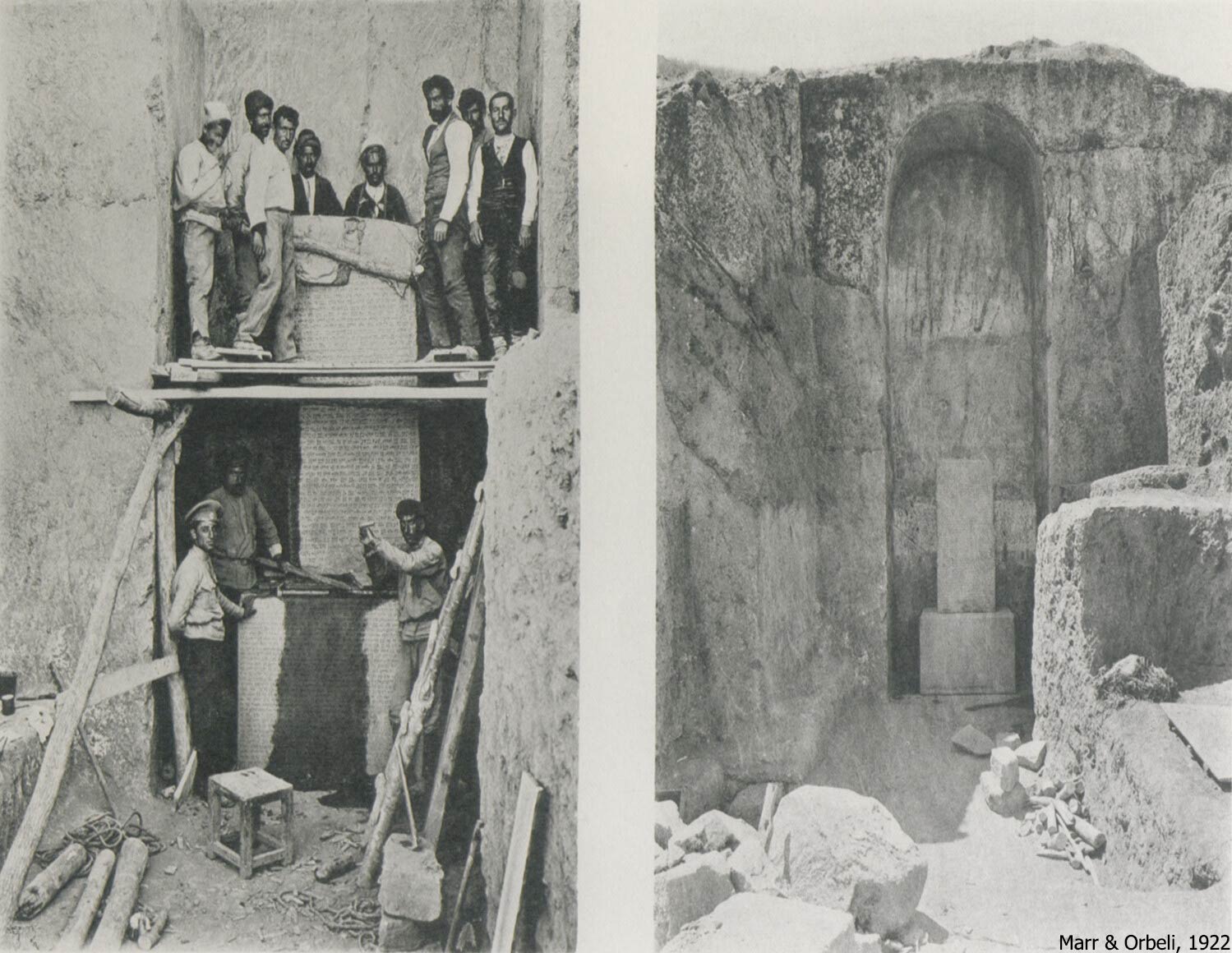

Analıkız Sacred Area

The site known as Analıkız (“mother with girl”) or Hazine Kapısı (“treasure gate”) is located on the northeastern slope of the citadel. It features a roughly 50-meter-long and 13-meter-wide rock-cut platform and two large niches carved into the bedrock. These names were assigned by the locals. According to O. Belli, the designation Analıkız derives from a local interpretation in which the higher eastern niche is associated with a mother, and the lower western niche with her daughter. The name Hazine Kapısı likely refers to the appearance of the niches, which resemble monumental doors believed to conceal hidden treasure.

The rock platform is carved more deeply on the western side than on the eastern side. A 0.5-meter-high rock bench runs along the northern, western, and partially the southern edges of the platform. When facing the niches, the one on the right—the western niche—occupies the deeper portion of the platform and measures approximately 8.10 meters in height, 2.60 meters in width, and 2.5 meters in depth.

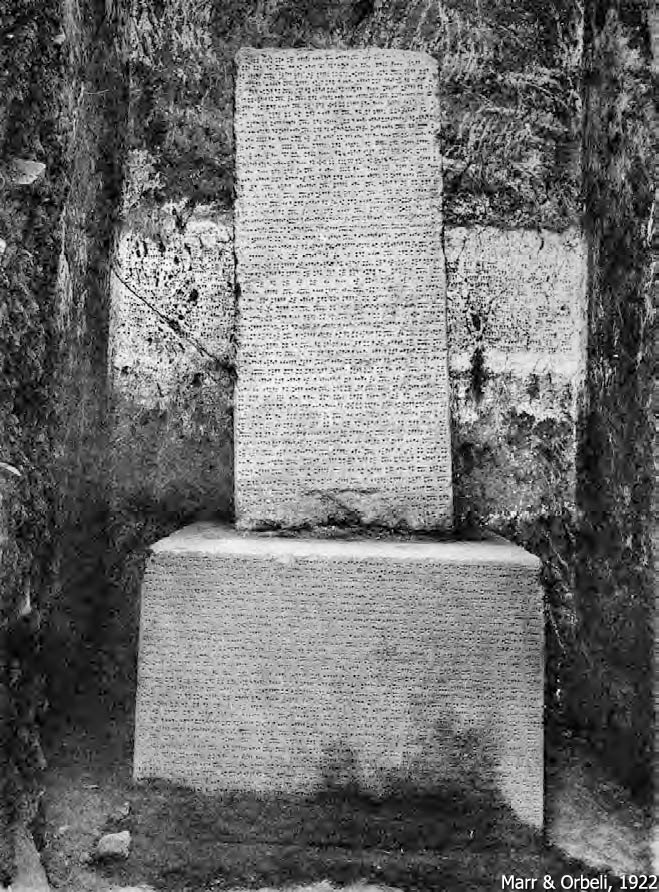

During the initial excavations conducted in 1916–17 by N. Marr and J. Orbeli, the bottom half of a large inscribed basalt stele, along with a rectangular base, was found in situ within this western niche (see image below). Both the stele and its base were damaged in the years that followed. Today, three large fragments of the base remain in front of the niche, while pieces of the stele are housed in the Van Museum. Additional fragments, believed to belong to the stele’s missing upper portion (A 9‑1 and A 9‑2), were discovered reused in the Surp Boğos Church in the old city of Van. The lengthy Urartian inscription—the annals of King Sarduri II (A 9‑3)—covers all faces of the stele, continues on the front face of the base and the back wall of the niche and ends on the upper left side wall of the niche.

The eastern niche, situated on the left side, measures approximately 6.15 meters in height, 2.60 meters in width, and 2.15 meters in depth. It bears no inscriptions. However, the floor of this niche contains a 1.5-meter-wide square recess with a deep mortise hole at its center, suggesting that it may have once held another stele.

According to researchers Analıkız was a sanctuary or an open-air temple used for cultic activities. Past studies also proposed that the canals visible on the rock platform may have been designed for rituals involving animal sacrifice. More recent research, however, suggests that the area was originally enclosed by walls and accessible only from the citadel. According to this interpretation, the channels were likely intended to drain water supplied from the citadel.

References:

Bachmann, W. 1913. Kirchen und Moscheen in Armenien und Kurdistan, Leipzig.

Belli, O. 2017. “I. Dünya Savaşı Sırasında Rusların Van Kalesi’nde Yapmış Olduğu Arkeolojik Kazılar ve Rusya’ya Kaçırılan Tarihi Eserler,” Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları, VIII – 21/2, 475-494.

Deyrolle, M.T. 1875/76. “Voyage Dans Le Lazistan et l’Arménie,” Le Tour Du Monde, Nouveau fournal des Voyages I, 369–416.

Genç, B. 2025. “The Archaeology, Description, and Possible Functions of the Monumental Memory of Ṭušpa, Analıkız,” in Tušpa: The Capital of Urartians, CHANE 143, eds. E. Konyar & B. Genç, Brill, 368-394.

Genç, B., K. Işık, A. Tan, H. Tümer. 2025. “The Siršini of Ṭušpa,” in Tušpa: The Capital of Urartians, CHANE 143, eds. E. Konyar & B. Genç, Brill, 267-279.

Genç, B. & E. Konyar. 2019. “Van Kalesi Analıkız Yapısı: İşlev ve Kronolojisine Dair Bir Değerlendirme,” Anadolu Araştırmaları, 22, 1–23.

Genç, B., A. Tan, C. Avcı, R. G. Akgün. 2025. “The Ṭušpa-Horhor Fountain,” in Tušpa: The Capital of Urartians, CHANE 143, eds. E. Konyar & B. Genç, Brill, 395-404.

Konyar, E. 2019. “A New Rock-Cut Tomb in Van Fortress/Tuspa,” Over the Mountains and Far Away: Studies in Near Eastern history and archaeology presented to Mirjo Salvini on the occasion of his 80th birthday, eds. Avestiyan, P. V. et al. Archaeopress, Oxford, 307-311.

Konyar, E. 2021. “Urartian Funerary Architecture,” in Archaeology and History of Urartu (Bianili) – Colloquia Antiqua 28, ed. G. R. Tsetskhladze, Leuven, 205-260.

Konyar, E. 2025. “Historical Topography of the Van Fortress,” in Tušpa: The Capital of Urartians, CHANE 143, eds. E. Konyar & B. Genç, Brill, 85-113.

Konyar, E., C. Avcı, B. Genç, A. Tan. 2013. “Excavations at the Van Fortress, the Mound and the Old City of Van in 2012,” Colloquium Anatolicum 12, 193-210.

Konyar, E., B. Genç, C. Avcı, R. G. Akgün. 2015. “Van Kalesi / Tuşpa Horhor Çeşmesi,” Colloquium Anatolicum 14, 66-75.

Konyar, E., B. Genç, C. Avcı, A. Tan. 2019. “Excavations at the Old City, Fortress, and Mound of Van: Work in 2018,” Anatolia Antiqua 28, 167-181.

Konyar, E. & B. Genç. 2025. “Buried in the Rock: The Royal Tombs of Ṭušpa,” in Tušpa: The Capital of Urartians, CHANE 143, eds. E. Konyar & B. Genç, Brill, 302-367.

Konyar, E. & B. Genç. 2025. “Ṭušpa from Dream to Reality: Pilgrims, Travelers, and Early Research,” in Tušpa: The Capital of Urartians, CHANE 143, eds. E. Konyar & B. Genç, Brill, 13-50.

Konyar, E., B. Genç, A. Tan. 2018 “Tuşpa Sitadeli’nden Yeni Bir Kaya Mezarı: BG 90,” Colloquium Anatolicum 17, 211-220.

Marr, N. Y., & Orbeli, I. A. 1922. Archeologiceskaja ekspedicija 1916 goda v Van, Russkoe Archeologiöeskoe Obscestvo, St. Petersburg.

Salvini, M. 2006. Urartu Tarihi ve Kültürü, çev. B. Aksoy, Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları, İstanbul.

Salvini, M. 2021. “The Written Documents of Ṭušpa, the Capital of Urartu,” in Archaeology and History of Urartu (Bianili) – Colloquia Antiqua 28, ed. G. R. Tsetskhladze, Leuven, 114-211.

Sevin, V. 1987. “Urartu Oda-Mezar Mimarisinin Kökeni Üzerine Bazı Gözlemler,” in I. Anatolian Iron Ages Symposium Papers, 24th – 27th April 1984, ed. A. Çilingiroğlu, İzmir, 35-55.

Sevin, V. 2012. Van Kalesi: Urartu Kral Mezarları ve Altıntepe Halk Mezarlığı, İstanbul.

Tan, A. 2025. “The Earliest Royal Building of the Urartian Kingdom: Sardurburç,” in Tušpa: The Capital of Urartians, CHANE 143, eds. E. Konyar & B. Genç, Brill, 212-251.

Tarhan, M. T. 1994. “Recent Research at the Urartian Capital Tushpa,” Tel Aviv, 21/1 (Iron Age Symposium on Eastern Anatolia: Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology 1992): 22-57.

Tarhan, M. T. 2011. “Başkent Tuşpa / The Capital City Tushpa,” in Urartu: Doğu’da Değişim / Transformation in the East, eds. K. Köroğlu & E. Konyar, İstanbul, 286-333.

Tarhan, M. T. 2021. “The Capital City Tushpa/Van Citadel,” in Archaeology and History of Urartu (Biainili) – Colloquia Antiqua 28, ed. G. R. Tsetskhladze, Leuven, 681-757.

Texier, C. 1842. Description de l’Armenie la Perse et la Mesopotamie–Van, Paris.

Image sources:

C. Texier, 1842

M. T. Deyrolle, 1875/76

W. Bachmann, 1913

N. Y. Marr & I. A. Orbeli, 1922

M. T. Tarhan, 1994

V. Sevin, 2012

O. Belli, 2017

B. Genç & E. Konyar, 2019

M. T. Tarhan, 2021

E. Konyar, 2019, 2021

M. Salvini, 2021

Ertuğrul Anıl, 2024

Bora Bilgin, 2024, 2025

Tayfun Bilgin, 2024

E. Konyar, 2025

A. Tan, 2025

B. Genç, 2025

B. Genç, et al., 2025

E. Konyar & B. Genç, 2025